Most of us have had the odd antibiotic in our lives. More recently your doctor might even have started prescribing something called flora – a tablet that the pharmacist will advise you to take every day whilst you are taking these antibiotics. And why is that? Well most of us now know that antibiotics not only target and kill the bad bacteria in our bodies, the ones causing all the trouble, but they also kill the good guys. And this is a problem for several reasons, which we won’t go into here. Suffice to say that putting the good bacteria back is vital for your gut health (more specifically the health of the gut’s microbiome) and digestion, amongst other things.

The role of the gut’s microbiome in maintaining our overall health has been studied extensively. However, the understanding of the microbiome on the skin is a little less fully developed. What has been discovered about the skin is that diseases are caused, not by bacteria or viruses, but rather by what is termed incorrect protein folding. Every process within the cell relies on proteins as they participate in virtually every process within that cell. When these processes or functions are impaired the results can be serious. Peter Karran (former principal scientist at the Francis Crick Institute in the UK and whose work has been focused on skin cancer) says that mutations accumulate over time and fuel the inevitably growing burden of oxidised proteins which contribute to the functional decline seen in ageing. Karran believes the key to unlocking treatments to extend healthy life may come from mechanisms that provide protection against protein damage.

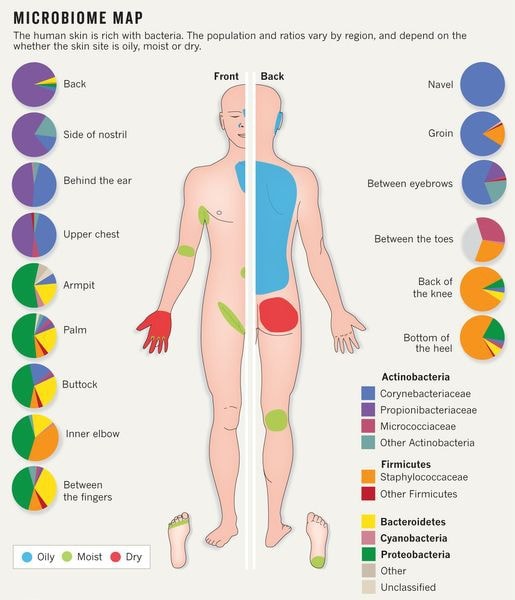

The skin is the body’s largest organ and serves as a barrier to our external environment. The surface of the skin is rich in microbes - a square centimetre of skin can contain up to a billion microorganisms. This is your skin’s microbiome - a community of bacteria, fungi, mites and viruses that provide protection against disease, as long as they remain in balance. Bacteria dominate this “skinscape” and are found on the top layers of the skin all the way down through the dermal layer. These populations can vary considerably on a single individual depending on several factors - temperature, moisture, pH, sebum content, UV light exposure and so on. The skin microbiome can be categorised based on skin type: sebaceous, moist or dry. The dry regions (forearm, palm or buttocks) have more proteobacteria, moist areas (nares, toes, armpits, etc) are dominated by firmicutes and sebaceous areas (forehead, back) are dominated by actinobacteria. These sebaceous zones are generally less diverse than either the dry or moist environments. Variations between individuals also occur, these are based on host factors (sex, age, ethnicity), environmental factors (humidity, UV exposure or temperature) and behavioural factors (like cosmetic and soap use). All these influences shape a person’s microbiome, which in turn has an impact on their skin’s health and appearance.

So why do these populations vary so much on one human body? The dry zones on your skin are the easiest to colonise and so have been found to have the richest diversity of microorganisms. The more sebaceous areas, like the face for example, are dominated by P. Acnes and have a much lower diversity of microbes. This is simply because sebaceous gland activity makes the skin in these areas a more hostile place for other microbes. I know you might be feeling right now that your body is being overrun with invaders, but this is not the case. The reassuring news is that overall your skin is an unsuitable environment for a great deal of microorganisms, in part due to the acidity of the skin’s natural barrier amongst other things. This means that a normal, healthy skin – whilst having a healthy microbiota - has a limited number of bacteria species that can happily live on it.

Within the microorganisms that do make a happy home on our skins you will find a couple of different types present. The first kind are what are called commensal microbes, meaning they co-exist without harming us. Others have a more interdependent relationship with us (we each benefit from the other). Interestingly enough some non-pathogenic microorganisms can harm us via the metabolites they produce (leading potentially to health issues depending on how our bodies react with these). Yet other microbes perform tasks that we don’t fully understand at this point. Those microbes that are expected to be found, and that under normal circumstances do not cause disease, are sometimes referred to as normal flora or normal microbiota.

The microbiome and skin

Research by the Human Microbiome Project has shown that the microbial balance on your skin has a key effect in anti-ageing and skin health, slowing down the ageing process whilst balancing and protecting your skin’s functions. A stable microbiome is essential to maintaining skin health. A higher degree of diversity in the skin’s microbiome is an indication of good health overall. People in urban, western cultures have less diverse microbiomes compared with those living in more remote or rural settings. The overuse of antibiotics in modern times is resulting in a higher incidence of skin allergies and skin conditions as this diversity and balance are compromised.

At last year’s Microbiome Symposium (5 June 2018), Magali Moreau, Ph.D., associate principal scientist for open innovation at L'Oréal, stated that (basically) the microbiome is not just an inhabitant of skin, it is actively engaged with it. When the microbiome is extremely unbalanced you end up with conditions like dandruff, acne and atopic dermatitis. Denis Wahler, Ph.D., global manager for technology partnerships at Givaudan Active Beauty, wondered whether consumers were ready for this type of technology. "Sixty percent of consumers are convinced of the positive effects of probiotics on health. And 41% of millennials are using probiotics in the United States; 45% of them are interested in trying probiotics for facial skin care." The answer appears to be: yes. Having established this, Wahler presented measurement techniques to assess the "stratum microbium" as he refers to it, and how a new technique known as nanopore sequencing could provide a total perspective. He felt the focus here would largely be in three main areas: “to balance and enhance the microbiome, through probiotic strategies; to protect the microbiome for fundamental skin health; and to trigger or activate the microbiome for different skin effects."

Aurėlie Guyoux (director of R&D at NAOS) believes we are overloading our skins. The cosmetics industry is using more than 30,000 ingredients in its products collectively. Many of these ingredients act as preservatives, i.e. they kill bacteria and other microorganisms in order to preserve the cosmetic products. They therefore also potentially kill the normal bacteria that is part of the skin’s biome. She also believes that you should align your skin products to what your skin needs, and what it will tolerate. In addition, with skin sensitivity on the rise, everyone should look to reduce their interaction with skin “pollutants” - many of which are found in cosmetics themselves. She also recommends that you don’t use products just for the sake of it. Take sunscreen for example - the lifespan of the chemical filter in sunblock is just 2 hours - so applying the sun protection first thing in the morning is irrelevant unless you are going straight out into the sun. Only apply SPF when you need it. Like sunglasses, do the same.

Eric Perrier, head of innovation at NAOS, feels that there are many compounds now that didn’t exist 100 years ago, and perhaps our bodies have not been able to adapt to the volume of them at the same pace. We are also eating at least a kilo of food containing endocrine disruptors. So, whilst what you put onto your skin is one part of the equation you must also understand what you are eating and the impact it will have on your system.

NAOS was founded on the principle of biology at the service of dermatology with the aim being to preserve skin health. “Eco-biology is based on the principle that the skin is an ever-evolving ecosystem that interacts with its environment, and whose natural resources and mechanisms must be preserved. Rather than over-treating the skin, it must learn how to function properly.”

It is tempting to think in simple terms - that there are good and bad microbes, but the reality is that skin microbes are much more complex and can act in either a beneficial or a harmful manner depending on the scenario (on a compromised skin vs a healthy one for example). In addition, a microbe might be benign in certain circumstances but could cause a skin response if it starts to increase in relative abundance - perhaps because other factors are out of balance. This microbial imbalance or maladaptation on or inside the body is known as dysbiosis.

Several studies have found disruptions in the skin microbiome on compromised skin - in these cases, a lower microbial diversity has been observed compared with that found in healthy skin. The same is true for chronic wounds. When damage occurs to the skin a local cascade of inflammatory signals, e. g., cytokines, are released in response to microbes that enter the site of injury (a breach of the skin’s protective function). Such changes in the local immunity drive signals that interact with skin microbes.

The microbiome changes as we age

The gut and the skin are interrelated - communicating with one another. The gut influences the skin, as we know when we look at people who have IBS and find they also suffer from atopic dermatitis or psoriasis. This link is now much more apparent.

The metabolites produced by the gut microbiome have an effect on the human system and form part of the mechanism that links the gut to skin health. The microbes in our gut love microbially accessible carbohydrates (for example fibre from tubers). We may not be able to digest and use these carbohydrates directly, but our microbes can, and they produce short-chain fatty acids from them. The colonocytes in our gut walls use part of what the microbes produce as their own fuel, namely gluterate macetate. This helps the colonocytes maintain an effective barrier between the gut and the lumen. Our diets have moved away from this sort of eating over time, leading to conditions like leaky gut which occurs when these colonocytes lack this fuel and the barrier cannot be maintained.

The skin’s microbiome varies between individuals, genders and ethnicity and depends also on where we live (altitude and geography). The microbiome plays a role in certain diseases like psoriasis, acne, atopic dermatitis etc. A study was done in Grand Rapids in 2015 on 500 individuals ranging in age from 9 to 78 to answer the question “what is the role of the microbiome in overall skin health & appearance?”. It was found the skin microbiome changes as we age. The study also discovered that two of the Corynebacteria found on the skin are associated with age - with one being found on younger people and the other on older skins. The two versions don’t exist at the same time, only one is present at any one time. The version of the bacteria found on older skins was also associated with skin redness - those with more redness in their skins had more of this organism, leading to red blotches and uneven skin tone

So how could we alter & optimise our microbiome to improve the skin’s health & appearance?

We know that our diets have a massive influence on our gut microbiome, but in the case of the skin, we know less about this area and the impact of topical products. What’s the total impact of preservatives in our skincare products or sunscreen on our skin’s microbiome? There are many products and ingredients that have been in use for some time in the cosmetic space that have not had any obvious adverse effects. There is also a fine line to be maintained between preserving products themselves to ensure their safety for use and minimising the inclusion of gratuitous and potentially damaging ingredients.

What about pollution or UV? Because UV can induce immune suppression these rays could have an impact on the microbiome - because immunity has an impact on the microbes. UV radiation can also affect the DNA of the microbes (the way it impacts the DNA of the keratinocytes of your skin cells). It is also likely that pollution has an impact on the microbes, but more studies are needed.

Does the microbiome interact with the epigenome? We know that our environment can cause epigenetic changes (like smoking does for example) so it’s likely that the whole of our microbiome organism could affect the epigenetics of human cells. Whilst your genome is static the surrounding environment affects you, and therefore your epigenome. Your microbiome links your body, through the gut & skin microbiomes, to the environment.

Is our innate microbiome the only factor here?

Kaoru Kasahara (POLA) explained at the IFSCC 2018 in Munich that bacteria in the surrounding environment also can improve barrier function, elasticity and skin brightness. He explained that everyone knows about the relationship between the bacteria everyone already has and the skin’s condition (for example P. Acnes and acne). But he goes on to mention the relationship between bacteria that NOT everyone has, and the skin. In his study, they measured the skin condition of 293 people and via TEWL tests found that 6 environmental bacterial species that were related to skin barrier function; 14 related to skin brightness; and 12 related to skin elasticity. The origin of these bacteria was looked at further and it was discovered that people in the “good skin condition” group had significantly more “outdoor-derived” bacteria than indoor ones. These outdoor derived bacteria that have a positive impact on the skin were then found to be from farm, and plant-associated, environments.

“Farm-originated M. Aerilata, which was related to skin barrier function—i.e., one of the 26 identified to improve TEWL tests, indicating good barrier function—[was isolated] to test its mechanism [of action]. It was added to the normal human epidermal keratinocyte [in vitro] and we saw an improvement in tight junction structure and skin barrier function.” In closing, he states, “we have also shown that lifestyle is one of the major factors in the amount of those bacteria, so we encourage people to incorporate plants into their life, and this could be a new approach to healthy skin.”

Unfortunately, it’s not clear which farmland and plant environments are most suitable for finding these bacteria - more tests and results will no doubt follow. But in the interim, it is probably worthwhile to make sure you spend more time outdoors, in forests or other plant-based environments, if you can. It will be beneficial for your soul and state of mind as well.

Let’s talk about yeast

“The same unicellular organisms that make kefir and croissants possible also live on the human body as part of the microbiome, members of the fungus kingdom coexisting healthily and happily with the billions of other invisible organisms (bacteria, viruses, even the occasional arthropod) that hold court on the skin's physical barrier.”7

But like everything in life, it is important to maintain a favourable balance between all these microbes. If you upset the microbiome’s biodiversity you will end up with increased inflammation and a change in the pH of your skin’s barrier. This, in turn, opens the door for unfavourable organisms and conditions to gain hold, for example, acne thanks to P. Acnes or an overgrowth of S. aureus leading to atopic eczema. And an overgrowth of the aforementioned yeast can lead to what is referred to (incorrectly) as fungal acne - an inflammatory condition called Pityrosporum folliculitis. The yeast responsible (Malassezia) thrives on sebum and is found in the sebaceous glands on the face, back, chest and shoulders. These lesions differ from acne vulgaris in that they are extremely itchy (sometimes with a burning sensation) and occur on the sides of the face and chin instead of in the centre of the face as with acne vulgaris. Consulting a medical professional is vital if your treatment for acne vulgaris is not having any impact, as you may need an antifungal medication as well as, or instead of, your acne medication. Generally, this yeast affects those living in hot, humid climates and is more common in males or those that sweat excessively. The use of lotions and sunscreen in summer can make this condition worse due to the occlusive nature of these products. The use of antibiotics to treat this condition is discouraged, as this can lead to a further overgrowth of the problematic yeast.

Cosmetics and the skin’s microbiome

The use of topical cosmetics, soaps and toiletries on the skin can have a marked impact on the skin’s microbiome, and we are only starting to understand these interactions more fully. Overuse of antibiotics and anti-bacterial products can potentially alter the diversity of these microorganisms and may even offer an opportunity for pathogens to increase on the skin. Of course, we aren’t suggesting you stop washing your hands. But perhaps we need to be more careful, especially with our faces.

The University of Pennsylvania conducted a study on mice involving the use of 3 topical antibiotics (bacitracin, neomycin and polymyxin). These caused significant shifts in the skin’s microbiome versus what was seen with the use of ethanol or iodide (antiseptics). This change in the microbiome left these mice more susceptible to S. Aureus infections, which are potentially lethal. The overuse of topical antibiotics can disrupt the epidermal barrier, and care must be taken.

Not all cosmetics have this negative impact on the microbes on the skin. As already mentioned, many cosmetic ingredients have been used in skincare products for decades without any negative side-effects, but as we learn more about the skin’s microbiome we must take the impact of future products and ingredients into account.

You may have noticed the trend of new formulations on the market that contain prebiotics or probiotics. But what does this really mean for skincare and your skin?

- prebiotics: the application of an ingredient that selectively allows for the growth of desirable microorganisms. In the context of the gut microbiome, this may include fibre or a type of polysaccharide. In the skin, prebiotics typically involve the inclusion of certain carbohydrates—for example, fructo-oligosaccharides. However, there is little evidence on the efficacy of topical prebiotics in the context of the skin microbiome.

- probiotics: this is the use of actual live bacteria, or a probiotic, on the skin. The topical application of S. Epidermidis, S. Hominis and other “beneficial” or benign skin organisms represents a significant opportunity in the cosmetic market for potentially reducing infections and improving skin hydration, moisture and pH. Whilst there are not currently many products available in this category right now it is no doubt an area that has potential and will be more thoroughly explored in the future as technological advances make it more feasible and practical to manufacture, store and distribute such products.

Finally, a place for HOCl

At Thoclor Labs we make a perfectly pure & stable version of Hypochlorous acid that goes into our Skin Series formulations. This HOCl supports the skin’s microbiome in several important ways:

- reduces inflammation, preventing certain bacteria from taking advantage of increased inflammation (like P. Acnes).

- reduces excessive sebum production, making the sebaceous glands less attractive for the Malassezia yeast.

- it maintains the skin’s barrier at the correct pH.

- acts as a microbiome friendly, discriminatory disinfectant - removing all “bad” microbes or pathogens (bacteria, yeast and viruses) whilst ignoring the “good” guys, helping to prevent an overrun of undesirable microorganisms.

- removes DNA-repair protein (which increases as we age) from the skin. This indicates a correction in incorrect protein folding, which is seen in ageing skin and leads to skin disease.

“It is increasingly apparent that our skin is not the first line of defence against the external world: that role falls instead to the army of microbes that live there. Keeping them happy could be the key to keeping our skin soft, supple and healthy.” (Martin Blaser, a microbiologist at New York University's Langone Medical Center)

Want to measure your own microbiome? Try Microbiome Insights

Sources

- Longevity Annual (2018-2019): Page 69-70.

- https://www.researchgate.net/scientific-contributions/38328606_Peter_Karran

- https://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/research/biology/podcast-Microbiome-Interactions-and-Skin-Health-Part-I-473636933.html

- https://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/research/biology/podcast-Microbiome-Interactions-Part-II-External-Forces-473856533.html

- https://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/research/biology/video-Freshly-Farmed-Bacteria-Boost-Skins-Barrier-502161681.html

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3970831/

- https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/fungal-acne-symptoms

- https://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/research/biology/The-Skin-Microbiome-A-New-Organ-and-How-to-Leverage-It-484677201.html

- https://www.cosmeticsandtoiletries.com/research/biology/The-Microbiome-Movement-Commensal-Cosmetics-Offer-a-Viable-Future-478318353.html

- https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/brainwaves/the-food-fight-in-your-guts-why-bacteria-will-change-the-way-you-think-about-calories/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4425451/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5585242/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_microbiota

- https://www.nature.com/articles/492S60a

- https://theecowell.com/blogs/well/skin-flora-101

Thanks for sharing this useful info and tips! Will keep it in mind!